All photos and images are copyright protected. Digital images and prints are available for purchase, please use the contact page or leave us a message below. All rights reserved

Queen Square sits just west of Bath’s busy central streets and marks the start of the city’s famous Georgian expansion. Built in the early 1700s, it set the tone for everything that followed, The Circus, the Royal Crescent, and the city’s reputation for elegant town planning.

This was the work of John Wood the Elder, a local man born and bred, who was destined to put his hometown on the map. Queen Square was his first step toward shaping Bath into a modern classical masterpiece. He used golden Bath stone, harmonious proportions, and an ordered street layout to create something new for its time.

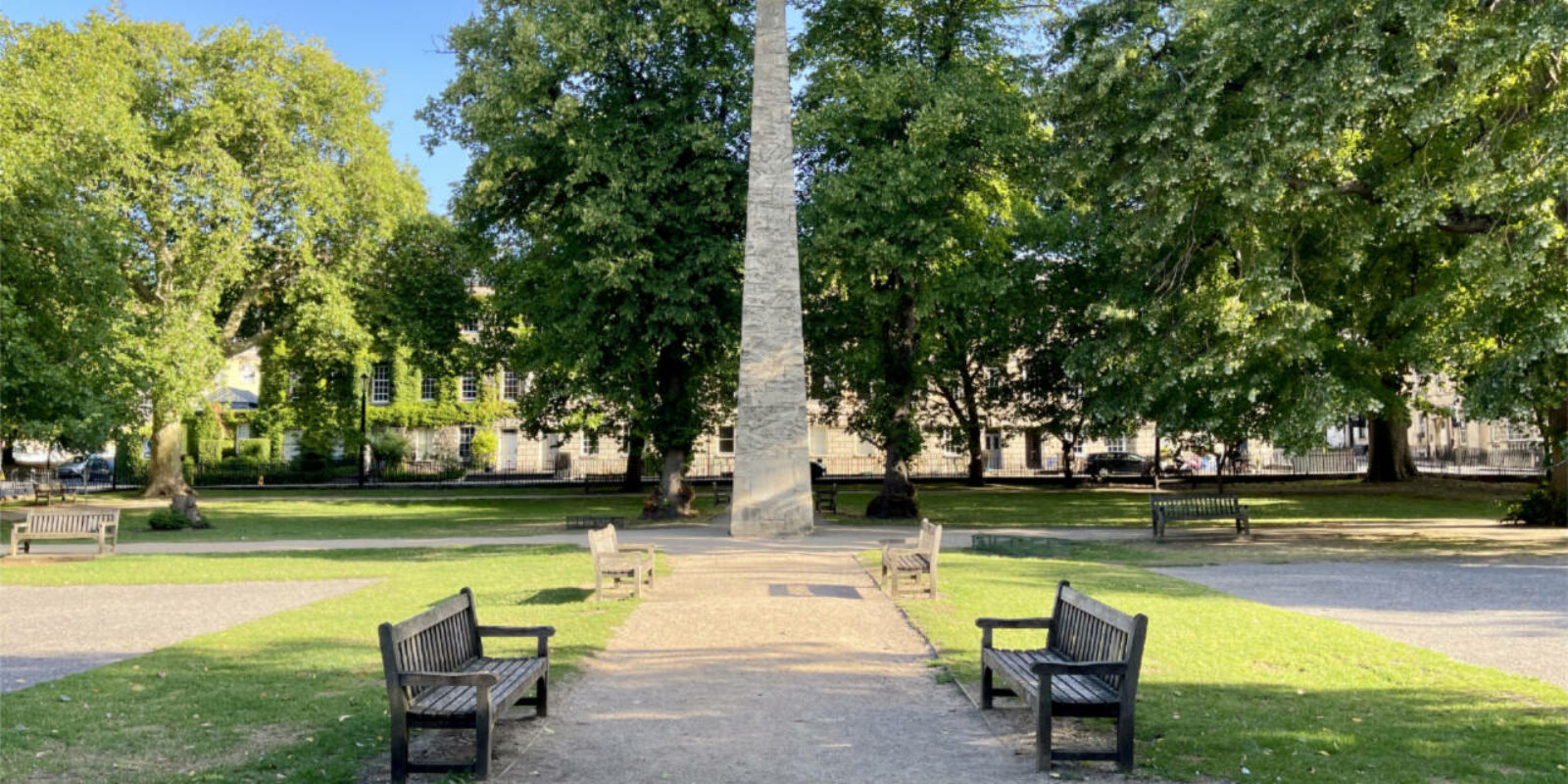

But there’s more here than symmetry and style. At the centre of the square stands a tall stone obelisk. At No. 13, Jane Austen stayed briefly during a family visit in 1799. Beneath the clean Georgian lines runs a quiet current of symbolism and philosophy, carefully placed by its architect.

Queen Square remains open to everyone. It welcomes you with benches, open views, and a sense of considered calm. It’s a good place to begin exploring Bath’s Upper Town—and a great example of the city’s layered character.

A Vision Realised: The Birth of Queen Square

In the 1720s, Bath was changing fast. The health-conscious elite had turned the spa town into a fashionable retreat, and local architects saw new possibilities. John Wood the Elder stood at the centre of this movement. He believed that cities could reflect beauty, harmony, and human ambition—all through careful planning.

Queen Square was his first major project. It was completed between 1728 and 1736, and it brought something new to Bath: a formal square built with classical principles in mind. Wood didn’t just arrange houses around a garden. He gave the north side of the square a unified façade, designed to look like one great palace. Behind it stood separate homes, but the exterior delivered a message of order and grandeur.

This “palace front” became one of Wood’s trademarks. It helped lift the tone of the city and attracted the kind of residents he hoped for—people with money, education, and a taste for fashionable living. The square also laid the foundations for a much larger plan. Wood saw Queen Square, The Circus, and the future Royal Crescent as parts of a greater pattern. Each space connected to the others in form, purpose, and meaning.

Further reading:

- Queen Square – Visit Bath

- Queen Square as an Outdoor Venue Bath and North East Somerset Council

- Historic England listing for 14–18 Queen Square

Sacred Geometry and Masonic Symbolism

From his prior experience and vision, John Wood’s work was far from only aesthetic. He studied ancient architecture, Druidic sites, and the geometry of temples. He also showed a great interest in Freemasonry, a movement grounded in symbols, sacred numbers, and a belief in universal order.

Wood’s writings point to these ideas. He admired classical philosophy, believed in the power of form, and looked to geometry as a language of truth. He saw Bath as a place that could carry meaning through its architecture and buildings.

Queen Square reflects this thinking. Its proportions are exact. The layout is deliberate. The obelisk at the centre, raised in 1738 to honour Frederick, Prince of Wales, may also carry symbolic weight. Obelisks were often used to mark spiritual or cosmic ideas in both Egyptian and Masonic traditions. In Wood’s plan, the square aligns with other parts of the city in a way that suggests both beauty and intention.

Later developments, like The Circus, would carry even more overt references such as circles, serpents, and patterns with deep symbolic history. But Queen Square is where that hidden language began. Wood built it for living, yes—but also for thinking.

Architectural Features of Queen Square

Queen Square introduced a new kind of urban form to Bath. Instead of building row by row, John Wood created a balanced, unified layout around a central green space. Each side of the square served a different purpose, but the north side stood apart.

This northern terrace, now known as 21–27 Queen Square, was designed to appear as one grand building. The uniform columns, pilasters, and windows give it the look of a stately palace. This was the first example of what would later become known as a “palace front” in Georgian architecture. Behind it, individual townhouses were fitted to a shared façade—a clever blend of private living and public elegance.

The other three sides of the square were more modest in design, but still followed classical principles. The uniform use of Bath stone, the evenly spaced sash windows, and the consistent roofline created visual harmony. It was this kind of planning that helped shape Bath’s identity.

Today, the square remains largely intact. Some of the buildings now house hotels, offices, and businesses, but the architecture continues to speak clearly. Walk its perimeter and you’ll see how Wood’s early vision took hold—and how the square became a model for later Georgian developments across Bath.

Key architectural highlights:

- North terrace (Nos. 21–27) – Architecturally it provides a unified palace front

- West terrace – Frontage of British Royal Literary and Scientific Institution (BRLSI) and other offices.

- Obelisk (1738) within Queen Square – central focal point with symbolic resonance

- Use of Bath stone – warm honey colour, typical of the period

- Balanced façades – classical columns, entablatures, and symmetrical windows

Best photographed in the morning when the light falls gently across the façades from the east side.

Jane Austen at No. 13 Queen Square

In the summer of 1799, Jane Austen stayed at No. 13 Queen Square during a short visit to Bath with her mother, her brother Edward, and Edward’s wife Elizabeth (Austens of Godmersham). Janet and her mother accompanied Edward to Bath for him to ‘take the waters’ for the benefit of his health. Their stay lasted just over a month, but it gives us one of the earliest glimpses of Jane’s personal experience of Bath.

In a letter to her sister Cassandra, written on May 17th, 1799, Austen mentions their lodgings:

“We are exceedingly pleased with our house; the rooms are quite as large as we expected and the furniture rather better than we looked for. The situation is also very pleasant. We are quite out of the noise, in the centre of things.”

— Jane Austen’s Letters, collected by Deirdre Le Faye

Queen Square offered them a convenient and respectable address. It was close to the fashionable streets and not far from the Assembly Rooms or the Pump Room. It would have suited their social standing while still being affordable for a short stay.

Austen’s tone in the letter is matter-of-fact, but it shows her attention to comfort and practicality, qualities she would later explore through characters like Anne Elliot and Elinor Dashwood. Her time at Queen Square came before her family’s permanent move to Bath in 1801, and while she wrote little fiction during this period, her observations of the city shaped the tone and detail of later novels.

Both Northanger Abbey and Persuasion feature scenes set in Bath. Austen’s knowledge of the city’s layout, social habits, and drawing-room manners was grounded in real experience. Even a short stay like this one helped refine her understanding of the place and the people who moved through it.

Further Reading:

- Letters of Jane Austen Edited with an Introduction and Critical Remarks by Edward, Lord Brabourne

- Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye

Tip: No. 13 stands at the far end of what is now The Francis Hotel. At the time of writing it is still a private residence and can be admired from the street. Combine a visit here with a walk to the Jane Austen Centre on nearby Gay Street for a deeper look at her life and legacy.

Queen Square Through Time: From Fashionable Address to Civic Landmark

When Queen Square was first built, it was one of the most desirable addresses in Bath. The houses attracted wealthy residents, many of whom came to the city for health, leisure, and society. The square offered quiet refinement just a few steps from the city’s main attractions.

By the early 19th century, the square had begun to evolve. Bath’s centre of fashion shifted west toward the Royal Crescent and Camden Place, and Queen Square entered a new phase. Several of the houses were repurposed. Some became boarding houses and small hotels, while others were adapted for professional offices. Despite these changes, the architecture remained largely intact.

The central garden was once enclosed by railings and managed privately. Today, it’s a public green space, open and inviting. The square often hosts events, including outdoor markets, small festivals, and heritage walks. It still holds a place in Bath’s civic life—less grand than in its early days, but no less appreciated.

Notable transitions:

- 18th century: fashionable residential address

- 19th century: shift to boarding houses and hotels

- 20th century: mix of commercial, civic, and public uses

- Today: heritage site and local green space

Even with these shifts, Queen Square has kept its character. Walk it now and you’ll see law offices, boutique hotels, and period-style guesthouses, all framed by original Georgian design. The sense of balance and quiet formality remains.

Visiting Queen Square Today

Queen Square is open to visitors year-round. It offers a quiet spot to sit, read, or enjoy a coffee before continuing toward The Circus and Royal Crescent. The open lawns and benches make it easy to pause, especially in the warmer months. Early morning and late afternoon bring the best light for photos.

The square is easy to reach from most parts of central Bath. It’s just a short walk from Milsom Street, the Jane Austen Centre, and Charlotte Street car park. Public buses stop nearby, and the main train station (Bath Spa) is a 10–15 minute walk.

The surrounding streets include a few excellent options for food and drink. Independent cafés, sandwich shops, and small restaurants make it convenient to stop nearby without straying far from the Georgian setting.

Visitor Tips:

- Good starting point for walking tours of Georgian Bath

- Close to Gay Street, The Circus, and Assembly Rooms

- Central obelisk and north terrace are popular photo spots

- Benches available in the central garden

- Free to visit, no tickets required

Suggested route: Start at Queen Square → walk up Gay Street → continue to The Circus → follow Brock Street to the Royal Crescent. This gives you a clear path through John Wood’s vision for Georgian Bath.

Nearby Attractions

Queen Square sits at the base of Bath’s Upper Town and makes a strong starting point for exploring the city’s Georgian highlights. Within a few minutes’ walk, you’ll find several of Bath’s most loved destinations.

- The Circus – A circular street of townhouses designed by John Wood the Elder and completed by his son. Its geometry and symbolism echo ideas seeded in Queen Square.

- Royal Crescent – One of the finest examples of Georgian architecture in the UK. Its sweeping curve and grand scale reflect the maturity of Wood’s vision.

- Jane Austen Centre – Located on Gay Street, this small but focused museum tells the story of Austen’s time in Bath. The building itself is Georgian and close to places she knew.

- Assembly Rooms – Once the heart of Bath’s social scene, these grand rooms hosted balls, concerts, and public events.

- Museum of Bath Architecture – A short walk from the square, this museum explains how Bath’s classical design came together—and includes a full model of the 18th-century city.

Each of these attractions builds on themes you first meet in Queen Square: order, ambition, and beauty shaped in stone.

Practical Tips for Visitors

Getting There: Queen Square is an easy walk from Bath Spa train station (approx. 10–15 minutes). Several bus routes stop nearby, and Charlotte Street car park is just around the corner.

Accessibility: The square is flat and fully open to the public. Benches are spaced around the central garden. There are dropped curbs at most crossings.

Best Time to Visit: Early morning offers calm and good light for photographs. Spring and early autumn bring colour to the square without heavy crowds.

Food & Drink: Local cafés, tearooms, and restaurants line the surrounding streets. Try Colonna & Smalls on Chapel Row for a coffee or pick up a takeaway from Milk Bun Deli on Queen Street to enjoy on a bench or try the Wild Cafe for something different.

Toilets: Public toilets are located nearby on Charlotte Street (small fee applies) and at Waitrose in The Podium.

Conclusion

Queen Square holds a quiet confidence. It doesn’t demand attention—but it rewards it. This is where Georgian Bath began to take shape. Walk its perimeter and you’re stepping through the early ideas of one of Britain’s most ambitious urban planners. Pause in the centre and you’ll find a space that still works, nearly 300 years after it was built.

Whether you’re following Jane Austen’s footsteps, studying classical design, or just enjoying a moment of calm away from the city’s busier streets, Queen Square Bath is worth your time. Start here and let the square show you the shape of the city past and that yet to come.